Element Six Denies Formal Deal on Japanese-Funded U.S. Diamond Factory: The Inside Story

In a significant clarification regarding the future of the global semiconductor supply chain, Element Six, the industrial supermaterials arm of De Beers Group, has formally denied the existence of a signed agreement to construct a Japanese-funded synthetic diamond manufacturing plant in the United States.

The statement comes in direct response to a widely circulated Reuters report earlier this week, which suggested that a deal was imminent as part of a broader diplomatic strategy between Washington and Tokyo. While Element Six acknowledges its technology was “referenced” in high-level trade discussions, the company maintains that no ink has been put to paper.

This development highlights a high-stakes geopolitical maneuver involving critical minerals, advanced technology, and the race to decouple from Chinese supply chains.

The Reuters Report: A “Tariff-for-Tech” Proposition?

According to the original Reuters dispatch, the Japanese government is exploring a massive financial package to support the construction of a synthetic diamond production facility on American soil. The report cited unnamed sources claiming that Tokyo aims to finance the factory as a strategic concession. In exchange, Japan hopes to secure an agreement from the U.S. government to lower tariffs on Japanese imports—likely targeting levies on steel and aluminum that have been points of contention in recent years.

The proposed facility would not be producing gemstones for engagement rings. Instead, it would focus exclusively on industrial-grade synthetic diamonds, a material increasingly viewed as a matter of national security.

Strategic Decoupling from China

The driving force behind this rumored deal is the United States’ desire to “accelerate domestic production” of critical materials. An unnamed source quoted by Reuters stated:

“By involving Japanese companies, Washington hopes to build a U.S.–Japan supply chain that does not rely on China.”

This objective is critical because China currently dominates the global synthetic diamond market, accounting for the vast majority of production via High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) methods. The U.S. and Japan are scrambling to secure independent sources of Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) diamonds, which are essential for next-generation technology.

Element Six’s Official Stance: “No Formal Agreements”

In an exclusive statement provided to JCK, a leading jewelry industry publication, an Element Six spokesperson sought to temper the speculation. While the company did not deny that high-level conversations are taking place, they were careful to clarify their current legal standing.

“We note that Element Six is referenced in connection with one of the potential projects mentioned in recent U.S./Japan trade discussions,” the spokesperson said.

They continued by emphasizing the company’s unique position in the market:

“As a leading producer of synthetic diamond and advanced materials for industrial applications, we recognize the critical role they play in enabling many industrial sectors. However, there are no formal agreements currently in place regarding any potential projects.”

This careful wording suggests that while Element Six is the preferred partner for this geopolitical initiative, the complex details of funding, location, and trade concessions are far from finalized.

Beyond Jewelry: Why Industrial Diamonds are the “Ultimate Semiconductor”

To understand why two global superpowers are negotiating over a diamond factory, one must look beyond the jewelry counter. Synthetic diamond is often referred to as the “ultimate semiconductor” due to its extreme physical properties.

Critical Applications in High-Tech Sectors

The “industrial purposes” mentioned in the Reuters report likely refer to several cutting-edge applications where diamond outperforms silicon and other materials:

- Thermal Management (Heat Sinks): Diamond has the highest thermal conductivity of any known material. As computer chips and AI processors become more powerful, they generate immense heat. Diamond wafers can dissipate this heat efficiently, preventing failure in high-performance computing centers and military radars.

- Quantum Networking: Synthetic diamonds with specific defects (such as Nitrogen-Vacancy centers) are the building blocks for quantum memory and sensors. This technology is vital for unhackable communications networks—a key priority for the U.S. defense sector.

- High-Power Electronics: For electric vehicles (EVs) and power grids, diamond semiconductors can operate at higher voltages and temperatures than traditional silicon chips, making energy transmission far more efficient.

The Portland Connection: Element Six’s Pivot in Oregon

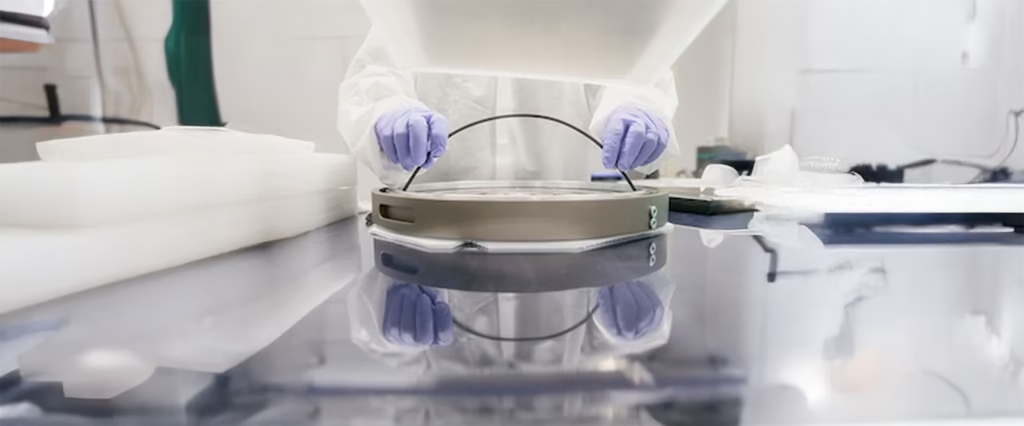

The rumors of a new factory are particularly interesting given Element Six’s existing footprint in the United States. The company already operates a state-of-the-art facility in Gresham, near Portland, Oregon.

From Lightbox Jewelry to Industrial Powerhouse

This Oregon facility was originally built to produce lab-grown gems for Lightbox Jewelry, De Beers’ consumer-facing synthetic diamond brand. However, following a strategic review and a crash in global lab-grown diamond prices, De Beers made a pivotal decision to shift the facility’s focus.

The Portland plant has been transitioning away from mass-market jewelry stones to focus on high-tech diamond applications. This existing infrastructure makes Element Six the most logical partner for any U.S.-Japan collaboration. Rather than building a factory from scratch, a “deal” could potentially involve expanding or upgrading the Oregon site with Japanese capital to scale production for semiconductor and defense clients.

The China Factor: A Race for Material Sovereignty

The backdrop to these negotiations is the growing tension between the West and China regarding critical minerals. China produces roughly 90% of the world’s synthetic diamonds, primarily used for abrasives in construction and manufacturing.

However, as the U.S. tightens export controls on advanced chips to China, Beijing has retaliated with its own export restrictions on materials like gallium, germanium, and potentially synthetic diamond substrates.

For Washington and Tokyo, relying on China for a material that is essential for defense radars, quantum computers, and future telecommunications is a strategic vulnerability they can no longer afford.

Conclusion: A Deal in the Making?

While Element Six is correct to state that “no deal has been signed,” the direction of travel is clear. The alignment of U.S. strategic interests (securing supply chains) with Japanese economic interests (lowering tariffs) creates a powerful incentive for cooperation.

Whether via a new greenfield factory or a massive expansion of the existing Portland facility, the production of synthetic diamonds is rapidly shifting from a luxury commodity to a geopolitical asset. For now, the industry watches and waits, but the groundwork for a U.S.-Japan diamond alliance appears to be under construction.